ZEN AND THE ART OF CERAMIC REPAIR,OR WABI-SABI KINTSUGI

By Cheryl Stevens

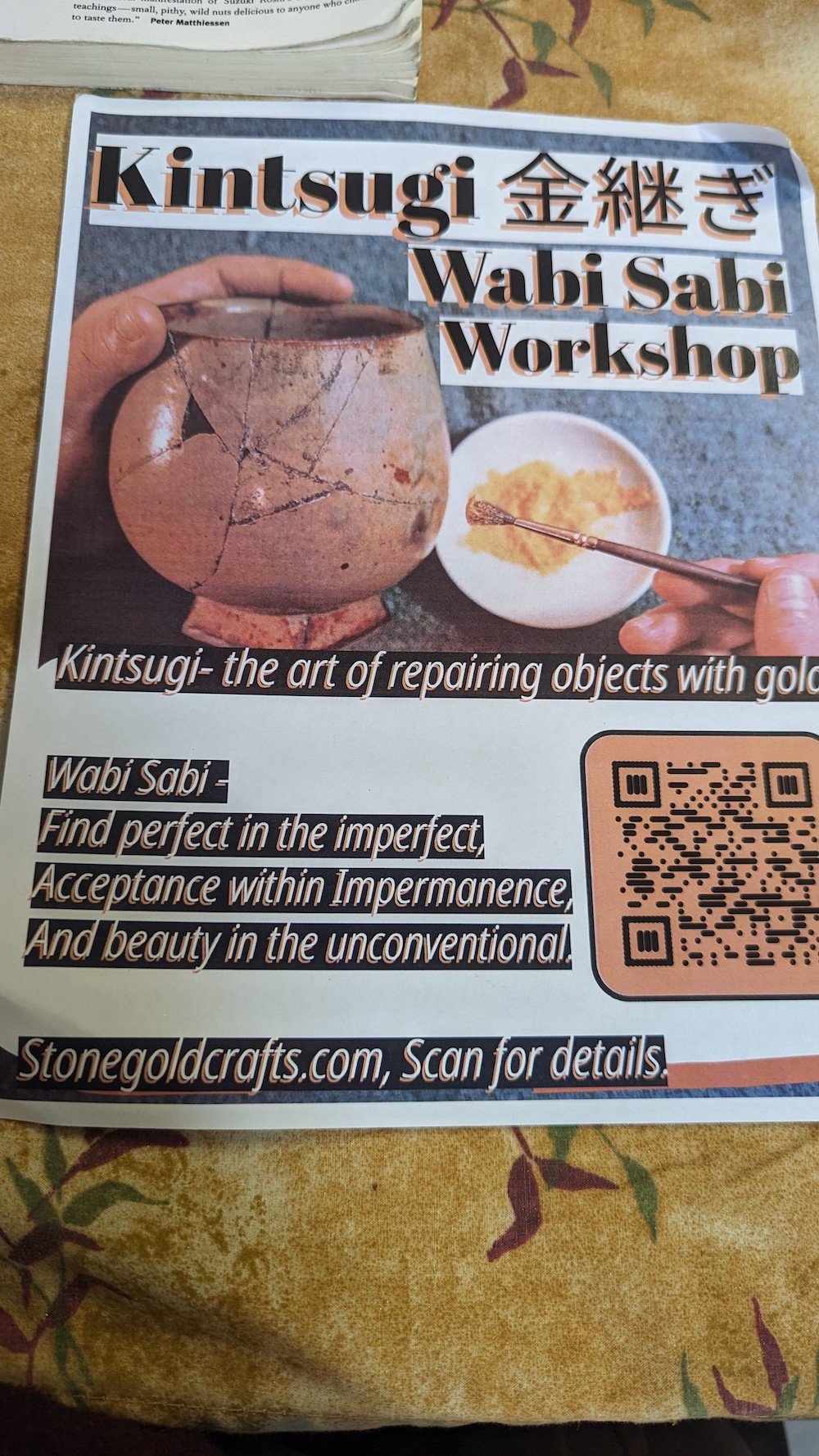

Recently at the studio, Ryley Gaulocher of Stone Gold Crafts taught two classes about wabi-sabi kintsugi, a beautiful way to repair broken ceramics. During each three-hour workshop Ryley discussed the Zen philosophy of wabi-sabi and the history behind the art of kintsugi as he guided participants through a contemporary version of this centuries-old practice.

Approaching the art of kintsugi requires an understanding of the philosophy of wabi-sabi, which allows us to become more closely connected to our true, inner self. Wabi-sabi encourages us to accept that perfection is impossible and to instead search for beauty in imperfection and surrender to the natural cycle of life.

Wabi and sabi are two separate concepts:

Wabi is about recognizing beauty in humble simplicity. It invites us to open our heart and detach from the trappings of perfection and materialism so we can experience true spiritual richness.

Sabi is concerned with the passage of time — the way all things grow, age, and decay — and how time manifests itself beautifully in objects. Sabi suggests that beauty is hidden beneath the surface, even in what we initially perceive as broken.

As a woman of a certain age, these two concepts immediately resonated with me. Finding a way to experience this peace or understanding while repairing broken ceramics or creating something new with my hands was definitely appealing. Identifying beauty in something damaged or broken and learning to acknowledge hidden beauty were, for me, the best takeaways from this workshop.

At the outset of the workshop, Ryley explained the more traditional method of kintsugi, urushi, which originated in China and relies on a lacquer made by extracting sap from the highly toxic sumac tree (a relative of poison oak). This older process is dangerous and contact with the lacquer frequently causes immediate skin irritation. Fortunately, Ryley instructed us in a modern method that substitutes epoxy resin for urushi and thus bypasses potential visits to the emergency room. The traditional urushi method is also more time consuming and involves multiple steps, including placing the pieces undergoing repair into a muro, or damp room, for several hours. We were able to complete the kinstsugi process from beginning to end over the three-hour workshop.

We started the class by breaking the piece we planned to work on — safely wrapped in a towel and dropped from waist height or higher. We then spent an hour on the first stage of the kintsugi process, a stage Ryley described as “inspection.” We sanded and prepared the broken shards and mentally reconstructed the damaged piece in a way that highlighted the imperfection created through destruction. It was during this process that I was able to explore the five principles of wabi-sabi. Namely:

Through acceptance, you find freedom; out of acceptance, you find growth.

All things in life, including you, are in an imperfect state of flux, so strive not for perfection, but for excellence instead.

Appreciate the beauty of all things, especially the great beauty that hides beneath the surface of what seems to be broken.

“Slow and simple” is the only way to feel the joy of what it means to be alive.

To be content exactly where you are, with all that you already have, is to be happy.

These five principles can apply to all ceramic work, but they really hit home when working to restore a broken piece in a way that included clear signs of the resulting imperfection.

The second stage, called fairing, involves filling the sanded gaps with adhesive (traditionally urushi, but in our class epoxy resin). In the final stage, maki-e (dust work), we worked gold powder into the cracks in the reconstructed piece. The illuminated golden highlights made the resulting “flaws” beautiful and taught us to appreciate the hidden beauty of the broken piece. We learned that we “had” to accept the final less-than-perfect product, and that our reconstructed pieces represented the perfect beauty accomplished through striving for excellence.

You may think this sounds like a bunch of mumbo jumbo, but I honestly believe the process really freed us to accept the outcome and that it truly illustrates the Japanese concept of shigatta ga nai, loosely translated as there is nothing you can do about it so accept it for what it is. At the end of our workshop I believe we all felt calmer — and pleased we’d been able to create something beautiful from objects that were once damaged and broken.

So, when you want to bring wabi-sabi into your life, to slow things down, and to embrace the beauty of imperfection, I can truly recommend you explore kintsugi and bring new life to your broken pieces. Perhaps we can apply wabi-sabi principles to other parts of our lives, too. We can definitely adopt wabi-sabi whenever we are in the studio, because it’s a concept that helps us accept the beauty of imperfection that lives below the surface whenever we create ceramics.

If you missed Ryley’s workshops, you can find a YouTube demonstration on his website. He also teaches a kintsugi workshop in San Francisco every Sunday. Ryley easily and clearly explains a process that for many seemed daunting at first but once he breaks the process down into manageable components while encouraging us to embrace the beauty of imperfection you will find yourself breaking everything in sight simply to put it back together again with the added illumination of beautiful gold highlights. So, don’t despair! There’s beauty below the surface of life’s imperfections — just turn to wabi-sabi to find it.

Special thanks to the students who graciously agreed to allow me to include their pieces in this article: Lisa Chen, Judy Haney, Ann Murphy, and Elizabeth Quayle. Thanks also to Ryley for taking the time to tell me more about the traditional aspects of kintsugi.